Parade Of Great Guitarists: Brother Wayne Kramer (1948-2024)

Ever hear of a band called the MC5? Let’s talk — if you read this ‘Stack, you owe this guy everything.

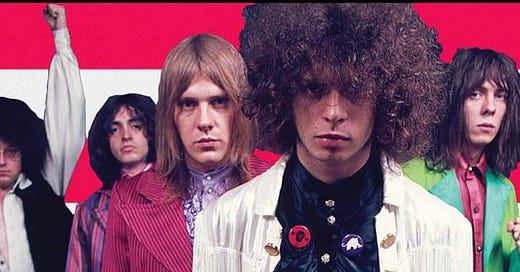

Children of the future, I give you a testimonial — THE MC5! Wayne Kramer is front and center, as he should be. (Pic: Raeanne Rubenstein)

Brother Wayne Kramer died, Friday February 2, 2024. And while I can’t imagine anyone who reads this Substack not knowing who Wayne is, I also wouldn’t want to know anyone who doesn’t. I also recognize I am grieving someone I considered a family member, and may be a little too hard-edged with emotion right now. So, let me soften up for a moment….

Once upon a time, in a mythic paradise called late ‘60s Detroit, there was a band called the MC5. Brother Wayne Kramer was their leader, a firebrand guitarist, half of one of the best two-man guitar tag teams in rock ‘n’ roll, alongside Fred “Sonic” Smith. Fred originally was the Five’s rhythm specialist, letting Wayne do all the heavy lifting in the lead department. Somewhere in their development, likely resulting from all the free jazz they were imbibing, Fred became an incredible lead guitarist in his own right. Yet rare were the occasions he’d take off on his own breaks. Wayne and Fred frequently worked in tandem, or side-by-side, playing counterpoint leads, like two saxophones going at one another on a jazz record. Or completely diverging from one another, taking the song in completely different directions that somehow formed a cohesive whole.

Which is a long way to explain that the MC5 were as much Sun Ra and Pharaoh Sanders as they were Chuck Berry, The Yardbirds and The Who. They were the incarnation of Lester Bangs' idea of a rock 'n' roll that combined the explosiveness of garage forebears like The Yardbirds with free jazz -- the emotional and the intellectual in one. Ironic, because as pointed out in this space two months ago, Lester’s “national magazine debut was a famously negative review of the MC5’s Kick Out The Jams in Rolling Stone. He’d revise his opinion in Creem two years later.” But that was Lester for you, always doubling back over himself, revising his blunt-force opinions when he realized he might be wrong. This is actually a strength, being as brutally honest about yourself as you are about some record, and publicly announcing your fallacies. I find that the way to go, really.

But the Five could also play Chuck Berry better than anyone this side of Chuck himself. Or, for that matter, the band universally accepted as Chuck’s greatest interpreters, The Rolling Stones. Probably because the MC5 always attached a Boeing jet engine to their Berryisms.

Which leads to the huge, hulking gorilla in the room that I am sure every last one of you has been expecting from me: Without the MC5, there is no punk rock. Period. (And c’mon, guys! I’m not THAT predictable!) The MC5 were the original Clash, without a doubt. But they were a Clash from the grimy industrial heartland town of Detroit, the sons of shop rats, bringing union-borne politics mixed with countercultural ideas to Marshall-amp-molesting rock 'n' roll. They even had an artist they trained to play bass in Michael Davis, just like Paul Simonon!

What’s more, the Five died for our punk rock sins. I’m serious! Were you subject to surveillance/harassment by local police and government intelligence agencies? Did you have your living quarters bombed? Was your hardcore band informed as you pulled up to various festivals to turn around, because the F.B.I. and local vice squad were there with warrants for your arrest? I didn’t think so. Nor was your band the one playing the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention, when bigger bands such as Jefferson Airplane chickened out. No, the MC5 showed up and played, as tear gas filled the air.

Frankly, their lyrical content played a large part in their becoming Persons Of Interest in law enforcement’s eyes. Because for all their American flag imagery, the MC5’s patriotism wasn’t blind. They just wanted our leaders to deliver their promises of freedom: “I learned to say the pledge of allegiance/Before they beat me bloody down at the station/They haven't got a word out of me since/I got a billion years probation/’69 America in terminal stasis/The air's so thick, it's like drowning in molasses/I'm sick and tired of paying these dues/And I'm sick to my guts of the American ruse.” But even Wayne admitted doing things like strapping on rifles alongside Fender Stratocasters in publicity photos may have been an ill-considered move as well: “Look at what’s happening now in the hip hop community,” he told me when Tupac Shakur was gunned down, adding, “Word to the brother.”

Speaking of Strats, and getting back to Wayne and Fred’s approach to the electric guitar, it’s important to note two things:

They were among the first rock ‘n’ roll guitarists to hot rod their axes. Nowadays, it’s so easy to take your Made In China Strat copy and replace everything, down to the bolts holding the neck. You upgrade it all, getting hotter pickups, more heavy duty wiring, whatever you need. In the late ‘60s, neither Larry DiMarzio nor Seymour Duncan were offering aftermarket guitar parts yet. So it was quite radical when Wayne and Fred installed Gibson humbuckers in their Strats and Rickenbackers and Mosrites, and Wayne had his Strat painted with a red, white & blue American flag motif. Ten years later, Eddie Van Halen was piecing together his own axes from surplus parts, shooting them with Schwin bicycle spraypaint, stripes built into his guitar graphics. The MC5 got there first, in the late ‘60s.

“The MC5 and The Stooges had a different approach to the electric guitar,” Wayne once told me. “We played the amp, too. Ron (Asheton, original Stooges guitarist) and I used to have discussions about this. You got your tone, your feedback, everything, by playing the amp. You turned it up LOUD, and used the overtones, the volume, the harmonics. The guitar was a tool you used to sculpt the sound, because you were playing the amp.” It’s interesting that the guys in the Five also stepped on no fuzz pedals or wahs, either, though Asheton certainly did, as did Jimi Hendrix, the other guitarist coming to mind who played his amp. Which meant Wayne and Fred were the purest, most unadulterated exponents of this ideal. Not to take away from the other amp players mentioned here, because you simply can’t. Just an interesting thing to note.

The MC5 were also one of the most universe-rupturing, mind-frying live rock ‘n’ roll outfits ever. Period. Don’t believe me?

That ain’t CGI. That’s the MC5. Gonna argue with me now?

Problem is, the MC5 only comprised nine years of Wayne’s life. Nine years out of 75 total, in Wayne’s case, is a drop in the bucket. True, the MC5 packed a lot into their brief moment, but that’s comparatively a gnat farting in a hurricane, placed in The Grand Scheme. What was Wayne doing the rest of that time?

A lot. He kept playing after the Five’s end, even as he became, in his own words, “a small-time Detroit criminal.” Beginning 1975, he served a four-year drugs charge in FMC Lexington – the subject of The Clash track “Jail Guitar Doors” (“Let me tell you 'bout Wayne and his deals of cocaine/A little more every day/Holding for a friend till the band do well/Then the DEA locked him away”) –- where he studied jazz under the tutelage of Red Rodney, one of Charlie Parker’s collaborators. Upon his release, Kramer played with everyone from Was (Not Was) to This Substack’s Patron Saint Johnny Thunders, in the short-lived-if-ill-advised Gang War. Disgusto-rock godhead GG Allin even managed to entice him and MC5 drummer Dennis “Machine Gun” Thompson into a one-off studio reunion, to cut a track called “Gimme Some Head.”

For several years and across several changes of locale, he worked as a carpenter and woodworker, still doing music when he had the time, including collaborating with Mick Farren on a rock opera based on a screenplay by William S. Burroughs, The Last Words Of Dutch Schultz. Moving to Los Angeles in 1994, he cleaned up after years of drug and alcohol abuse, signing with Epitaph Records and releasing a series of fine solo albums. You could do worse than cue up either The Hard Stuff (featuring The Melvins and my old pals Claw Hammer among his accompanists), Dangerous Madness or Citizen Wayne, or even all of them back-to-back. All represent some of the most mature, adventurous rock ‘n’ roll ever recorded.

He entered the 21st century still recording and touring, including a few treks around the world with reconstituted MC5 lineups. Besides penning an excellent memoir also called The Hard Stuff, he mostly concentrated on scoring films and TV, and co-running his non-profit Jail Guitar Doors — providing musical instruments and lessons to the incarcerated — with wife/manager Margaret Saadi Kramer and The Bard Of Barking himself, Billy Bragg.

It’s my belief that Jail Guitar Doors was the key to understanding Wayne’s true nature. Like most who had one foot in punk and the other in the ‘60s, his form of resistance embraced a certain openness and generosity of spirit. He was giving, he didn’t take without putting something of his own on the table. He picked up his guitar to cry against oppression, yes, and to speak truth to power, not for personal glory. But more so, his Strat fought for those trapped in the same darkness he once knew. Through Jail Guitar Doors, he brought the healing power of music to incarcerated individuals. He saw the humanity behind the bars, the potential for redemption, and he gave them a voice, a chance to scream, to express, to heal.

He also built community and family among those he encountered along the way. I know, from personal experience. After I interviewed him for Alternative Press around the time he was promoting The Hard Stuff album, The Hormones were booked by The Electric Lounge to open the Austin date on that tour. Thereafter, I was in. When he returned to town and had a little time before he needed to play his gigs, he’d call up. We’d have lunch, share good conversation, maybe go book shopping: “Oh, Alvin Toffler — you need to read him, Tim!” (Come to think of it, I could stand to re-read Future Shock, the classic work by the man who coined the phrase “information overload.”)

He took The Hormones with him through Texas in the summer of 1997, when he was promoting Citizen Wayne. We all worshiped Wayne and the MC5, of course – Ron Williams decided he had to join forces with me when I perfectly executed Wayne’s first “Looking At You” guitar lead. We were all shocked no one was showing up for the gigs, despite me doing everything in my power to promote the shows to our mailing list in all the towns we played — Dallas, Austin, and Houston. But every night, he stood in the wings watching us with a huge paternal grin. And all of us in The Hormones felt like we were being paid $150 per night to get a guitar lesson! I know I learned how to play octaves and emulate echoes without a delay pedal, just by watching Wayne’s fingers.

Two weeks later, we played all the same towns on our own as headliners, to packed clubs. Every gig on that jaunt, I asked the crowds, “Where were you two weeks ago, when we came through with Brother Wayne Kramer?!” Invariably, some wag answered: “Who?”

“Yeah,” I’d sneer, “that’s what I thought….” I was more blunt to a reporter from The Houston Post two weeks earlier: “Houston’s punk scene just shit all over its father, and everyone claims to be such a ‘huge fan’ of the MC5.”

He was another poster on my teenage bedroom wall who became my friend. More than that, he was family. He wasn’t “Brother Wayne Kramer,” to me. He was Uncle Wayne. Anytime I ended up in the hospital (and there was a five year stretch at the turn of the century where I was in the hospital annually), he’d find out and he’d call me. I probably interviewed Wayne 10 times over the 29 years I knew him. It was always a joy, and I always learned something from him. The last time was last summer, interviewing him about the MC5 for my punk book. He told me it was high time I wrote a book. I think it will now be dedicated to him.

Yeah, Brother Wayne Kramer is gone. To you, he was Brother Wayne. But he was my Uncle Wayne. And I miss him, badly. I’d dare say the whole world misses Uncle Wayne, whether they realize it or not. I suggest we all honor him by continuing his good works:

Donate to Jail Guitar Doors and bring the power of music to those who need it most.

Support independent music venues and underground artists.

Raise your voice against injustice, wherever you see it.

Live your life with the same passion and authenticity that Brother Wayne Kramer embodied.

But even if you just play guitar like you’re wielding a Thompson machine gun, mowing down the politics of hatred in a bullet-shower of distorted notes, you are continuing his good works. And I hope his epitaph reads: Let me be who I am, and let me kick out the jams, yeah….

#TimNapalmStegall #TimNapalmStegallSubstack #PunkJournalism #ParadeOfGreatGuitarists #BrotherWayneKramer #MC5 #Legend #RockNRollRevolutionary #WayneKramerTribute #GuitarHero #PunkRockPioneer #JailGuitarDoors #LegacyOfUncleWayne #KickOutTheJams #MusicForJustice #RememberingWayneKramer #GuitarInnovator #DetroitMusicIcon #WayneKramerForever #RockNRollActivist #WayneKramerMemories #GuitaristExtraordinaire #MC5Forever #WayneKramerInspiration #PassionAndAuthenticity #SupportIndependentMedia #NapalmNation #Subscribe #FiveDollarsMonthly #FiftyDollarsAnnually #UpgradeYourFreeSubscription #BestWayToSupport

I remember going to see him play at Electric Lounge in '97 or '98. I was extremely puzzled by how poor the attendance was. He put on a killer show. The MC50 show was a pure joy to attend.

I remember that book signing Tim! I could tell how very happy you were. Good work Tim.

Yay! I was looking forward to reading your thoughts on Brother Wayne to complement mine: https://cjmarsicano.substack.com/p/brother-wayne-kramer-has-rambled.

As usual, Brother Tim, you did fantastic work. I hope mine measures up somewhat to yours.