SPOT (1951-2023)

Sorry if I am not more creative in my titling. But punk rock has lost one of its greatest producers, the world has lost one of its great characters, and I have lost a dear friend.

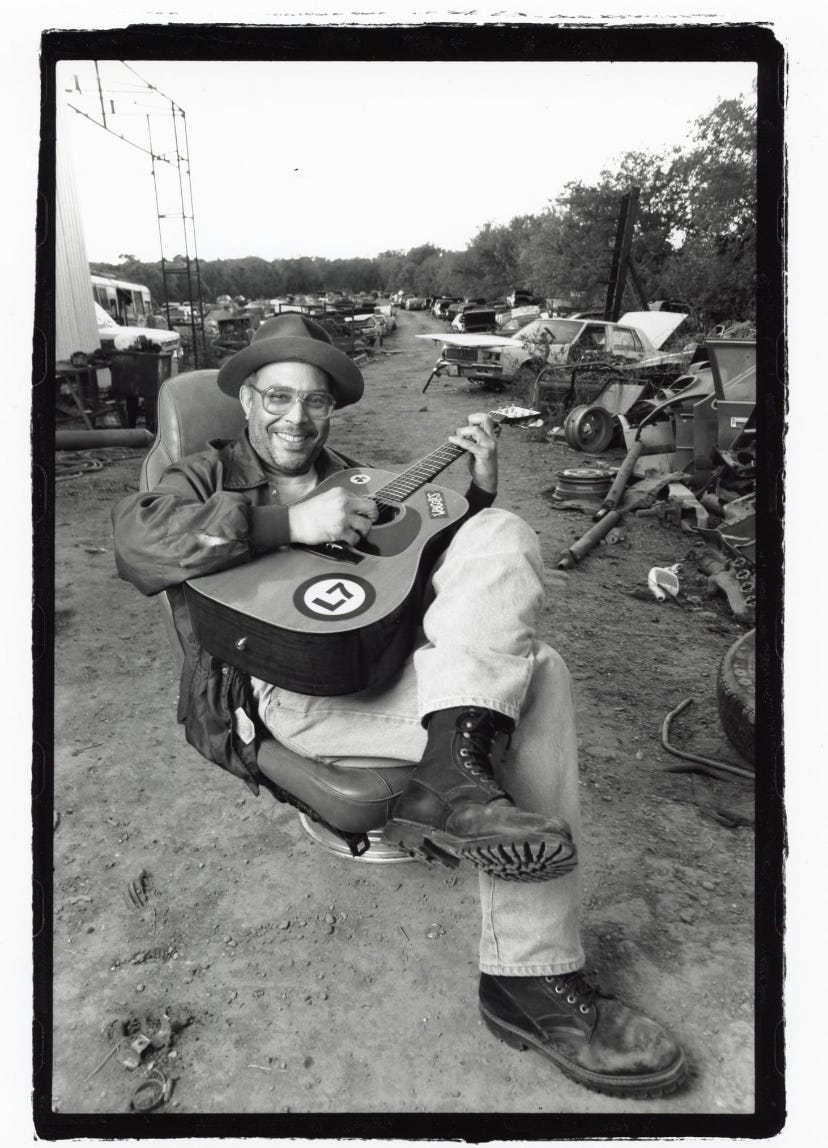

Glen Michael Lockett, better known to the world as SPOT, July 1, 1951 – March 4, 2023. (Pic: George Brainerd)

48 minutes past noon Saturday, former SST Records A&R man/co-owner Joe Carducci – who has particularly articulated the aesthetic and philosophy behind that titan in Eighties American independent labels, likely even better than leading lights Greg Ginn and Chuck Dukowski – took to his Facebook page to announce to announce that Glen Michael Lockett, best-known to the world as classic SST in-house producer SPOT, had lost the good fight he’d been fighting against fibrosis and a stroke 2 hours earlier. He was 71. (You can read the post here.)

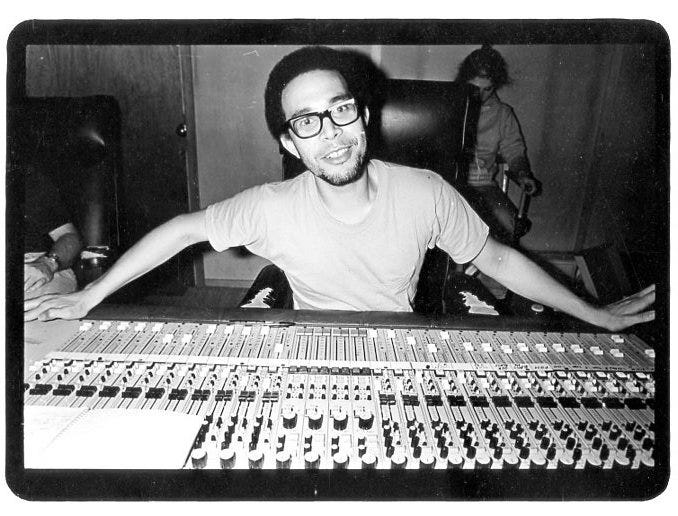

By now, you can read any number of wonderful tributes or full-on obits to the man who produced every crucial SST record, be it by Black Flag, Minutemen, Hüsker Dü, or whomever. These obits range from my buddy CJ Marsicano’s wonderful essay at his own Substack, to The Austin Chronicle’s own Chad Swiatecki-penned observance. Even Pitchfork, Variety and Rolling Stone weighed in, all seemingly using photobill’s shot of SPOT showing off the mixing board at Austin’s Third Coast Studio during the 1982 sessions for the Big Boys’ Fun Fun Fun EP.

SPOT at Third Coast Studio, Austin Texas; March 14 1982 - Big Boys "Fun Fun Fun" session. (Pic: Photobill/Bill Daniel)

SPOT also cut a who’s who of American punk and hardcore bands, who engaged his services after maybe hearing Black Flag’s Damaged, such as Descendents (who admittedly were SST adjacent for much of their early career) and Misfits. Then there’s all the Austin bands he cut even before relocating here in the mid-Nineties – Big Boys, Dicks, The Offenders and Hickoids come to mind. You can get a better grasp of the scope and depth of his productions by looking at his Discogs page.

In short, there’s a lot of posthumous information out there, which does my heart good. Because while the punk world lost a tremendous and skilled technician who defined one of the best approaches to how a punk record should sound, the general world lost one of its great characters. And many of us on the ground lost a great friend. Including me.

I knew from profiling SPOT (always capitalized, with a dot in the middle of the “O,” if he was signing something) for the Chronicle in the early ‘90s (an article that is sadly not archived on the website) that he was a native of Los Angeles, born in 1951 raised in the Crenshaw neighborhood. His father, Claybourne Lockett, was one of the Tuskegee Airmen, flying British Spitfires in WWII. His mother was Native American and grew up in New Orleans. Among his high school classmates: George and Louis Johnson – funk legends The Brothers Johnson, of “Strawberry Letter 23” fame. According to Rolling Stone, he first picked up the guitar at age 12, and once auditioned for Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band.For someone as wide-open and Catholic in his interests as SPOT, it’s absolutely believable that his first musical love was jazz. He stated in a comprehensive conversation with Red Bull Music Academy, “I’d been raised listening to post-bebop jazz. Going back into the ’50s, I’d be at family barbecues where they’re playing Thelonious Monk, and stuff like that.” Come the ’70s, SPOT was “really enamored with a lot of what I guess you would call progressive rock. That whole era with concept albums, when jazz fusion started happening, before it turned into bullshit.”

“I was interested in following this path that I thought was the right path,” he continued. “It was about being sophisticated, and really exploring music, and being as good as you possibly could be…without watering it down into something that’s just about making money or being popular.”

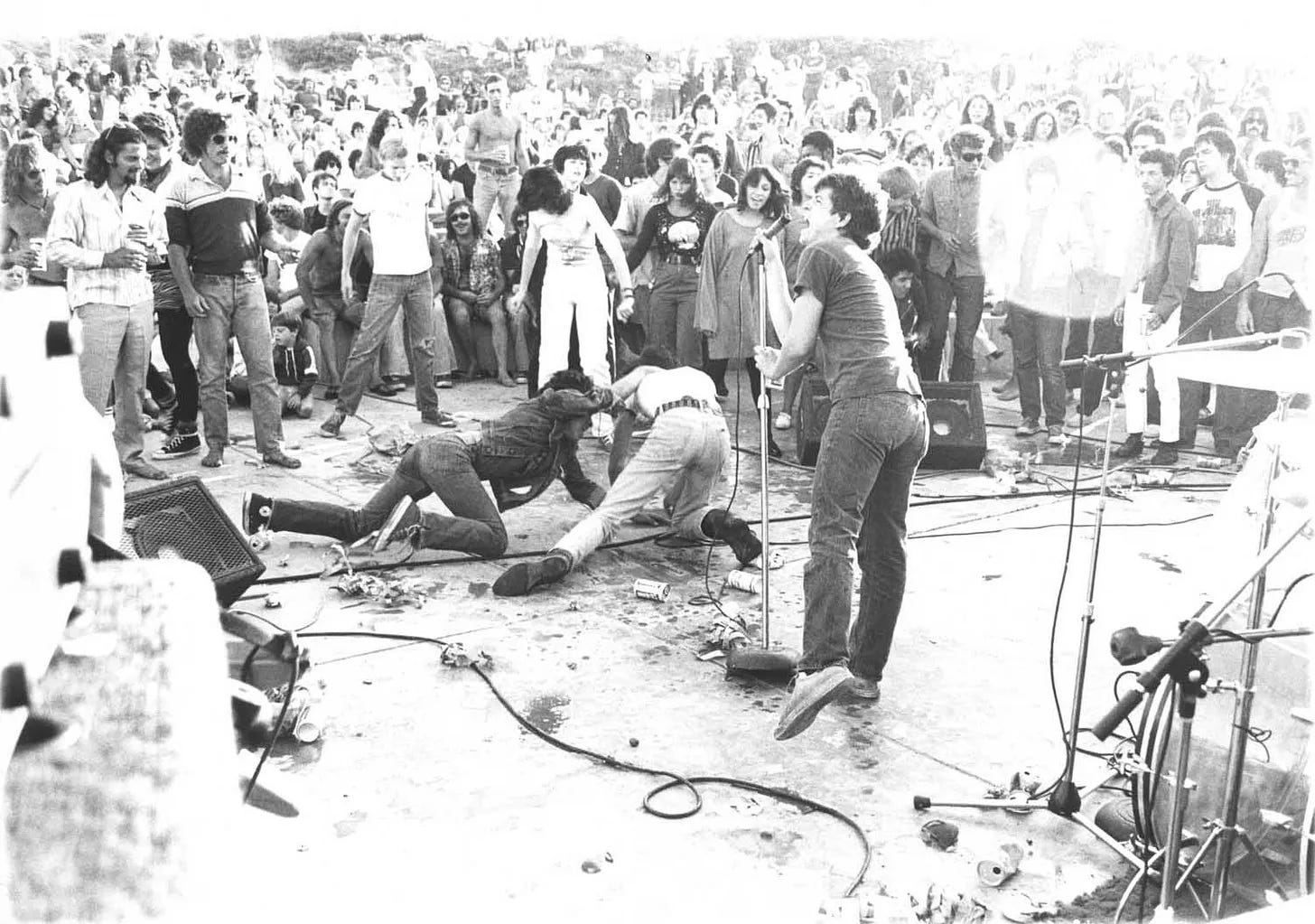

He wasn’t so enamored of this sophistication by the time he ended up in Hermosa Beach in the mid-’70s, writing about music and taking photographs for the local alt weekly Easy Reader. It was there he stumbled across punk rock via the Ramones’ debut album. He saw a kinship with the jazz he was already advocating in the paper, and dove into the deep end, playing briefly with a budding Hermosa Beach punk band, Panic. After he left and they changed their name to Black Flag, he watched their legendary lunchtime gig at Polliwog Park, where their antagonistic, chaotic tunes caused picnicking families to hurl the contents of their lunches at the band. (Dukowski, SPOT’s replacement in the band, apparently scooped up the Glad-bagged sandwiches for the next few days’ subsistence.)

“I’ve got to record this band before they get killed.” SPOT reportedly thought to himself as he watched the sandwiches fly.

1979: Then-Black Flag singer Keith Morris — yes, this Substack’s hero for the last few months — standing firm during the infamous Polliwog Park melee. Wrestling in the slop of what sandwiches Chuck Dukowski did not scoop up: Future BF vocalists Ron Reyes and Dez Cadena. Capturing the mud, the blood and the sandwiches: The skilled camera lens of SPOT.

“He started in Hermosa Beach playing and recording jazz and he took the primacy of live jazz playing into recording bands against prevailing attempts to soften or industrialize a back-to-basics arts movement in sound,” wrote Carducci two days ago. Translation: SPOT approached a mixing board less like Phil Spector and more like D.A. Pennebaker – he was less a producer and more a documentarian. He wasn’t gonna tell you how to play, or change your arrangements. He was going to record you, in the most stark, realistic, minimalist way possible.

“SPOT worked for you and could do whatever you wanted,” Big Boys/Poison 13/Bad Mutha Goose/Monkeywrench/Jack O’Fire/etc. guitarist Tim Kerr – who developed a considerable production hand, himself – told the Chronicle’s Swiatecki. “He would suggest things, but he knew how to get things sounding the way you wanted. He was all about getting the sound you wanted coming out of the amp rather than relying on a bunch of stuff inside the studio like adding all kinds of reverb. Then he’d mic it up close and then find a sweet spot farther back…I learned how to do that from being around him.”

“Ever try micing a 100 megaton blast?” SPOT wrote of working with Black Flag on the Everything Went Black liner notes.

As the ‘80s ground on and even the most abrasive underground band wanted to adopt that gawdfersaken gated reverb/overly compressed recording orthodoxy that stank up the radio the entire decade, some of SPOT’s clients might have thought they could “do better.” Maybe he was too “lo-fi?” Truth be told, not one of them ever improved on his ultraloud, sawtooth wave guitars, subterranean bass, and banging drums, all going to tape as dryly as possible.

“We had to go in there, get things set up quick, go through the tracks quick, and then get the stuff mixed quick, because that was all the time and all the money we had to work with,” SPOT explained the methodology to the Red Bull interviewer. “It had to get done.” Budgets, whether for time or to pay the studio for that time, were microscopic, so a quick and dirty approach was required.

“Everything was based on the idea of playing the music right when you were playing it live, and then recording that,” he said. Re: Hüsker Dü’s breakthrough 2xLP Zen Arcade? “The entire session, from basic tracks to final mix, was roughly about a hundred hours. Which is not very much time at all. None of it was perfect. But we just had to get it done.” And that 100 hours was done straight through, on pots of coffee sweetened with methamphetamine, according to Bob Mould

All good things come to an end, and the SPOT/SST alliance screeched to an end in 1986. “The dynamic of how the label functioned, under that model, just didn’t work too well,” he said. “I worked with them until I kinda couldn’t work with them anymore. It’s really sad.”

Once he relocated to Austin – one of Black Flag’s favored tour stops – in the mid-’80s, he found a vein of bands who liked the way SPOT produced just fine: Kerr’s post-BIg Boys Poison 13 and Bad Mutha Goose And The Brothers Grimm; Jeff Smith and Davy Jones’ destructo punktry and western outfit Hickoids; and a whole slew of groups associated with Rabid Cat Records, including political thrashers The Offenders – who were combining hardcore and brutal dentist-drill metal when Metallica were barely a Lars Ulrich wet dream – Not For Sale and The Texas Instruments, who played garage-folk rock as loud and fast as the Ramones, through Peavey amps rebadged with Friedrich’s air conditioner logos.

He continued producing local Austin groups probably until just before he left town in 2008, though he really concentrated on his own musical endeavors as his 22 years here wound down. Jesus Christ Superfly leader Rick Carney posted at Facebook the other day a fairly typical tale about working with SPOT on the local trad-punks’ third LP, 2004’s I Don’t Wanna Be Crazy:

“We were at Million Dollar Sound with SPOT producing and Kurtis D. Machler engineering,” he wrote. “There was no visual connection to the recording booth and the control room. Ron Williams was cutting a lead vocal. After an attempt I heard SPOT on the talkback mic, ‘Ron, it sounds like you are reading the lyrics off a piece of paper.’ (Anyone who knew SPOT read that in SPOT’s distinctive voice). Stunned, I looked at Ron and he said ‘I was! Ha ha ha!’ (And anyone who knows Ron read that in his equally distinctive voice.) Ron was singing his heart out, but SPOT could hear that there was more in the tank. SPOT was amazing to work with and a genuine and generous person.”

The word around town was that the man did not want to talk about Black Flag or SST. Greg Ginn owed SPOT (and many others) a substantial amount of money, and he was not happy about it. But SPOT inevitably would talk about those days anyway, under his own steam, usually with one of his offbeat observations related in that hilarious, distinctive voice that made me think I’d met my first live action animated cartoon character. And it was always something like, “Chuck Dukowski played bass like a guy who’d unzipped his pants and pulled his dick out, and he wanted you to notice his dick was hanging out!” Or comparing another band’s sound to “one of those old Otis elevators, if they’re well-maintained. It’s just solid, and everything clicks into place.”

He once phoned me up about a week before The Hormones were to open for his early ‘90s band, SPOT Removal.

“Tim, we should have a poetry slam as part of the show.”

I was kinda puzzled. “What? We let people read their poems?”

“Yes,” he replied, “but while they’re slamdancing and stagediving.”

“Ohmigawd,” I laughed. “You mean they shout a line as they skank past the mic on their way to jump off the stage?!”

“Yes!” he guffawed. “Exactly!”

This is the SPOT whom I and many others knew intimately. This guy who played many instruments virtuosically, including the “fidola” – a viola played like a fiddle. Who tried to play the clarinet with Black Flag in Mike Muir’s garage, banjo with ‘90s garage punks The Shindigs, and turned his performance at a Ramones hoot night I organized into a parody of Junior Brown, after the country guitar genius walked out two minutes into an interview I attempted with him. (“Yall jest thank ah’m an asshole anyway!” he drawled after his Western Swing version of “I Wanna Be Sedated.”) The man who could play anything from free jazz to Celtic jigs and reels on any instrument, and could play it well. Who could repair any Volkswagen. Who’d go in for a morning shift behind the griddle at Magnolia Cafe, pouring himself a cup of coffee concentrate – not the coffee, but the undiluted concentrate! Who, when I told him I’d just bought a plexiglas Dan Armstrong guitar a la Greg Ginn, observed, “Well, I guess that’s alright, as long as you wear pants while you play it.” Who left Austin for Sheboygan, Wisconsin, to be closer to an apparently thriving Celtic music scene I know I had no idea existed, until SPOT told me about it.

Glen E. Friedman’s camera captures SPOT watching on as Black Flag destroys Suicidal Tendencies leader Mike Muir’s garage in 1983. SPOT hadn’t yet decided to add his clarinet.

What I especially miss is the SPOT who sat with me at a table at the Hole In The Wall one night as Jesus Christ Superfly ripped into Iggy And The Stooges’ “I Got A Right.”

“Y’know, Jesus Christ Superfly is a good band,” he observed. “But they aren’t playing the song right.”

I looked at him with what was probably a classic puzzled dog look. “They’re playing it wrong?!”

“Everybody does,” he replied. “Everybody plays it as if it was a hardcore song. And it’s not. It’s a gospel song. It has that groove.”

He was right. SPOT was always right. And this world has no idea what it lost the other day.

I miss my friend. A bunch of us miss our friend. We want him back. Please.

#timstegall #timnapalmstegall #timnapalmstegallsubstack#punkjournalism #spot #obituary #blackflag #sstrecords #minutemen #huskerdu #joecarducci #descendents #misfits #dicks #bigboys #theoffenders #hickoids #brothersjohnson #rabidcatrecords #thetexasinstruments #notforsale #jesuschristsuperfly #punk #hardcore #subscribe #fivedollarmonthlysubscription #fiftydollaryearlysubscription #bestwaytosupport

Excellent read. "Spot on", you might say. JCSF did in fact play I Got A Right incorrectly. We were using the Murphy's Law arrangement. Plus, at the time I couldn't play that cool little bass walk up that Ron does on the chorus.

This is a GREAT write up and send off to a truly one of a kind character and Tim Stegall could not tell SPOT's story any better! R.I.P. Mr. Lockett...........